"Transmittal" Note for Thesis

Amateur Road Racing in Michigan was written to fulfill the requirement for a thesis in the Masters Degree program at the University of Michigan in the American Studies Department. I had set out to write "The Career of Empiricism in American Political Thought", which elicited a big yawn from my advisors. Dr. Robert Houbeck, director of the library at U of M Flint invited a very dynamic speaker to address the group of us electing to do a thesis. Dr. Gleaves Whitney was and is the Director of Grand Valley State University's Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies and was the State Historian during the John Engler administration. He spoke to each of us individually and after listening to my proposal, he commented that all my research was going to address was a shelf of books. He asked me what I cared about.

I hope it shows in Amateur Road Racing what I care about a lot. The Webmaster offered me the opportunity to edit it, to rewrite some sentences that seem clumsy and tedious to me now, but I've decided to leave it as is. The University's requirements were that I demonstrated the ability to show reasonably professional research and writing ability and that I addressed topics my advisors thought appropriate to the field of America Studies. Why certain events and people were "featured", and others not, served that end. WHRRI by itself deserves a book and it would take a book to address the cultural richness of the Club. The Rackham School of Graduate Studies gave me an 'A' and the degree.

There is a great deal I would change in style, sentence and paragraph structure, but there are now better things to do; the facts and my sentiments are unchanged and are stronger today than ever. One of the hopes of the founders of the Oakland County Sportsman's Club was that it be an institution for conservation of dearly held American values and virtues. Road racing was pretty obviously not what they had in mind at first; but taking into account the changes in American society after the founding, through the Fifties and Sixties and then since, OCSC and WHRRI have succeeded in fulfilling that hope.

• • •

AMATEUR ROAD RACING IN MICHIGAN

THREE INSTITUTIONS

By RICHARD RANVILLE, JR.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- A Definition of Road Racing

- History of American Racing

- The American Road Racing Renaissance

- Janesville Airport

- Grattan Raceway

- Gingerman Raceway

- Waterford Hills Road Racing

- Conclusion

- Reflections

- Appendix

INTRODUCTION

This thesis discusses certain topics in the subject of amateur road racing in Michigan. This project was substituted by the author for a more traditional academic topic after a chance discussion with a speaker in a research class that was part of the Masters in Liberal Studies in American Culture program. This project is in part historical but it attempts to be a history that connects developments in the sport to broader themes in the study of American culture.

This thesis focuses primarily on three institutions. Waterford Hills Road Racing is a club, founded in nineteen fifty eight near Clarkston Michigan in the shadow of the capitol of the American automobile industry. Waterford dates back almost to the beginning of the modern sport and in its history has reflected developments in the sport. Grattan Raceway in Belding Michigan is a family business. The founder and owner, who as of this writing, still lives on the grounds, operates the track, renting it out to many clubs and other groups. He and his family help stage events. Grattan also dates to early times in the sport. Gingerman Raceway in South Haven Michigan is comparatively new. Gingerman is owned by an individual who is an enthusiast, but Gingerman is first and foremost a business. The development, promotion and operation of the track are very different in many ways than either Waterford or Grattan, and more deliberately parallels modern corporate practices. Together these three offer an interesting study of certain elements of American culture.

These three are most significant in one important respect. They are the only "landed" road racing institutions surviving in the State - that is, institutions that own a track. They have required the investment of lives and resources. They are each different in how that has been done. In addition, the stories of their foundations and development are unique. They still exist and are thriving in what remains a niche sport, in a day when American racing is dominated by NASCAR. Their stories touch on just about every significant development in the sport. Some activities illustrate fault lines in American culture. For example money dominates vintage car racing, lately strong growth element in the sport, while club racing focuses on participation at whatever level one can attain. Money and amateurism have been issues in the history of races sponsored by the Sports Car Club of America, whose Detroit chapter holds its races at Grattan and Gingerman on the west side of the state, but not at Waterford, the club.

The sport itself has a unique and colorful history, populated with unique and colorful people. This thesis expects to be in part the story of several remarkable and interesting people.

It begins with a history of racing in the United States. This section sets the context for the development of amateur road racing. Road racing, as it emerged in the late nineteen forties was in many ways a deliberate repudiation of popular American racing practices. For many years about the only things road racing and the rest of American racing had in common were four wheels and a steering wheel. Only in recent years have the sports converged in important ways.

The presentation digresses to an extent with a discussion of the nineteen fifty two sports car races at Janesville Airport in Wisconsin. The program for that event is reproduced as an appendix. While not a Michigan event, this program illustrates all of the elements surrounding road racing events generally. The organizational structure has carried over to modern practice and anyone interested will see substantially the same elements at a race meeting today. The style of presentation of the Janesville races, the period advertising convey a deep sense of the times and the culture in the early days of the sport. This thesis must ultimately concern itself with the emergence of themes in American culture; besides providing sharply focused context for later developments, the section on Janesville Airport provides the interested reader the opportunity to vicariously visit the early days of the sport.

The thesis then turns to the history of the three institutions in Michigan discussed above and considers whether their stories inform us about American culture at large.

AMATEUR ROAD RACING DEFINED

None of the institutions considered here would exist as they do today, nor would they have developed as they have, if the sport contested were not road racing. "Road racing" became, through the process discussed below, a culture, and a specific definable approach to motor sports and to the culture of the auto industry. But first it was simply an alternative form of the sport. Road racing was, in the beginning, quite literally that: races that were held on public roads both here and in Europe. As the sport developed and cars became faster and more powerful, the roads were blocked off from public access for the race. Local officials most often acquiesced with these arrangements in return for the publicity and business generated by the races. Crowd control and safety issues, as well as in convenience, made closed course racing more desirable. In addition, closed courses offered business opportunities that Americans were quick to realize and so most of American racing quickly turned to closed race courses. Albert R. Bochroch writing in his American Automobile Racing says there were few, although interesting, American road races after nineteen seventeen, and the last reference was to the activities of ARCA, the Automobile Racing Club of America.1 During the period ending about nineteen thirty four in the United States, commercial interests and safety issues confined American racing to closed, purpose built tracks.

Road racing was and is conducted in all weather, on all manner of road conditions - paved or not, concrete, brick; and races were conducted at night, the courses illuminated by the headlights of the cars. Road racing began as a test for cars designed to be driven on the road in the conditions encountered by ordinary drivers. As the sport developed, mainly in Europe, the cars became more specialized in the ways necessary to enhance performance. But the all weather, all road conditions requirement remained. Public road courses remained popular in Europe; as late as the nineteen nineties the famous races at LeMans, in France and Spa Francorchamps in Belgium were held on public roads blocked off for these famous races. And the Grand Prix of Monaco on the French Riviera is still held today, on the streets of Monte Carlo. The glamour and sophistication of these European events played no small part in the post World War II renaissance of road racing in the United States. In American Road Racing John C. Rueter, a member and competitor in ARCA in the nineteen thirties and forties, says the group openly copied European practices.2

As we will see, road racing emerged in this form briefly after World War II. The same concerns that arose in the early days of racing eventually led to the construction of purpose built road racing courses. These courses mimicked road conditions, with turns of various shapes and the best courses incorporated hills and other natural features.

The subject of amateurism has been as an important topic in sports for a very long time. This thesis does not attempt to engage that discussion. With minor exceptions in track rentals, the institutions discussed here were created to serve amateur automobile racers, people who are not paid to compete, who compete for the love of the sport. The Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) went to great lengths, sometimes thought absurd, to exclude paid professionals from the sport. The SCCA eventually founded a separate professional series to accommodate those who demanded paid participation. The people whose stories are presented here are people who compete for the love of the sport and the sense of fulfillment resulting from competition. The achievements of some of them are all the more impressive in consequence.

HISTORY: AMERICAN AUTOMOBILE RACING

There is a cliché in the sport that racing started when the second car was built. Racing, both in Europe and the United States dates back to the earliest days of the industry. A popular trivia question is: Who won the first automobile race held in Michigan? The answer is Henry Ford, in 1901, on the Detroit Driving Club's track in Grosse Point Michigan.3 The National Automotive History Library, a department of the Detroit Public Library, has original photographs from the event.

Current American racing lore has it that road racing developed in the late nineteen forties and took a firm place in American sports history from there. That view is wrong in a couple of important respects. But the reincarnation of the sport in the eastern United States is the heritage that predates the events in Michigan that are our main subject and the entire sport as it is conducted today.

There were road racing events in American history before World War Two but changes in American culture, discussed below, resulting in part from the war, helped define what road racing became. American racing before and after the war was and is dominated by oval track racing.

The Indianapolis 500, first run on August 19, 19094, epitomizes American oval track racing in every important respect and has since its beginning. The track is roughly rectangular with four well rounded, regularly shaped corners. It is in an enclosed facility so access can be is carefully controlled. Admissions could be charged and were from the earliest days. The closed facility also makes emergency services easily and quickly available and facilitates communications on race conditions.

Spectators could see most of the course from the grandstands, at least in the early days. Concessions were added over the years, providing additional attraction for the spectators and additional income for the owners. Garage facilities for the racers were installed and eventually became elaborate. Sophisticated "pits" were developed where cars could come off the track during events for service and reenter the race. Spectators were afforded limited access to these areas, at an extra cost. Over the years guard rails and other barriers to protect spectators were developed.

The cars started the race in formation, rolling at a speed below racing speed until the green flag was thrown to start the race. The cars went around the track in a counter clockwise direction. The races are not held in inclement weather and the Indianapolis 500 has been halted for rain several times, to be refinished on a later day. Racing is not conducted in the dark; in later years lights were installed to light the entire track for night racing. All of this describes in the essentials the way most American racing is conducted today.

Oval track racing was a big business from the early days of the sport. Americans were well accustomed to sporting events in closed venues. Baseball and football, as well as boxing and even bicycle racing were popular going into the early days of auto racing. Closed venues allowed for efficient crowd control, but primarily facilitated charging admission fees and, as developed notably in baseball, for the development of concessions as additional sources of revenue. Barney Oldfield, later a famous auto racing driver, was a successful bicycle racer early in his career.5 The fabulous, but dangerous, wood board tracks popular after World War I showed the direct influence of bicycle racing on auto racing.6

As the automobile spread, so did racing and countless cities, small towns and villages across the country. Auto races were first held on horse racing tracks and it is said the use of these tracks set many of the features auto racing, including the American habit of running races in a counter clockwise direction. Some tracks became elaborate small scale versions of Indianapolis; many more remained multi use county fair type facilities. Many tracks were and are privately owned and developed.

At many levels of the sport, from the earliest days, drivers were paid professionals. Smaller venues, down to the crudest local "bull ring" often paid prize money. Amateurism was a hot topic in some American sports around the turn of the century, but did not become much of an issue in auto racing until the founding of the Sports Car Club of America in the 1940s.

Almost from the beginning American racing became and remained for many years the province of purpose built race cars. As in Europe, the major manufacturers built race cars, often using components from production cars. Ford, Buick and others entered racing. The primary motivation was promotion and sales. "Looking back on his racing experience, Henry Ford said "Winning a race or making a record was then the best kind of advertising".7 The major auto companies participated through the 1920s, but with cars very different from those they sold to every day motorists.

Racing cars became single seat vehicles after increases in reliability eliminated the need for riding mechanics. Engines and transmissions became more specialized but therefore less flexible and less suited to every day driving. As the cars started the race rolling at speed, self starters were eliminated and the cars were hand cranked, pushed to start or started with plug in machines. At most important levels and venues, purpose built race cars designed and built by specialty producers came to dominate racing. There is little doubt that production based "jalopies" were raced in small venues around the country. But the spread of Midgets, literally miniature versions of big league race cars, and Super Modifieds, single seat cars with custom fabricated chassis powered by highly modified production engines, provide support for the view that "real" race cars were specialized vehicles. At least, they were until the advent of stock car racing.

Stock car racing is conducted at the national level by the National Association of Stock Car Racing (NASCAR) and by numerous local sanctioning bodies and tracks around the country. It is the largest, richest and most popular form of racing in the United States today. The singular difference between stock car racing and the other major forms of racing in the United States is that the cars look like the cars motorists drive on the streets. One of the oldest maxims in the automobile business is "Win on Sunday, sell on Monday". Stock car racing has taken maximum advantage of the race cars' similarity to cars sold to consumers. The modern sport grew out of the moonshine running days of prohibition. Purpose built race cars would be immediately suspect (and eventually illegal) on public roads. Every day cars were heavily modified to carry the loads and to provide additional performance to be able to outrun the police. Fords were the favored cars before World War II, much to the consternation of prohibitionist Henry Ford.8 Prohibition ended, but the production and distribution of moonshine remained popular in the southern United States and the popularity of racing coupled with the mechanical and driving skills developed set the stage for the creation of NASCAR and stock car racing. This period is well documented in Deal with the Devil by Neal Thompson.9

Two important facts pertinent to our topic come out of his development. The first is that stock car racing was born and became popular among working class Americans. NASCAR and other promoters have made every effort to maintain that association even though the teams, owners and drivers have become very wealthy. The second is that the cars were never "stock", meaning left just the way they came from the factory. From the beginning, they were heavily modified to enhance performance. Thompson remarks: "From the beginning, of course, racing purely stock cars had proved impossible, with wheels falling off, radiators exploding, and engines seizing. Race promoters and sanctioning bodies made allowances for such non-stock alterations as larger radiators and stronger lug nuts to keep the right side wheels from tearing off. Without such allowances, they'd never have had enough cars for a good race."10 As we will see, this was a marked difference from the imported "sports cars" involved in post war road racing. The "stock cars" of today are purpose built race cars that bear only passing resemblance to the cars people drive on the streets.

The ascendance of stock car racing highlighted an important distinction in racing, that between cars with fenders ( or "closed wheel" cars), and therefore ostensibly, close to passenger cars in important respects, and "single seater" or "open wheel" race cars, purpose built race cars. Despite every real and cosmetic dilution of technical and performance differences, the belief persisted for a long time that "real men" drove open wheel race cars and that legend permeates every brand, level and version of American racing today.

Stock car racing was for most of its existence has been conducted on oval tracks in exactly the same way as open wheel racing. Beginning in nineteen fifty nine with NASCAR founder Bill France's Daytona International Speedway, the premier level of the sport has been conducted on "super speedways" with banked turns that accommodated speeds of over two hundred miles per hour before financial and safety concerns led to restrictions. Only after road racing had been reestablished as a vital part of American racing did NASCAR and American stock cars return to road courses, now among its most popular venues. Interestingly, that return to road racing came at Watkins Glenn, the birthplace of post war American road racing.

Finally, stock car racing involved strictly American cars until two years ago, 2006. The step into NASCAR by Toyota was contemplated with the usual Japanese caution and study.

THE AMERICAN ROAD RACING "RENAISSANCE"

The putative birth of road racing in the United States occurred at the upstate New York town of Watkins Glenn on October 2, 1948.11 The race was officially staged by the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA), but in fact was largely the promotion of an individual member, Cameron Argetsinger.12 He was assisted by small group of opportunistic, non SCCA member racers. Some of these were members of ARCA, the pre war road racing club.13 And he had the enthusiastic support of an opportunistic community, which saw a way to bolster tourism. These same kinds of forces led in a few years to the establishment of road races in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, Bridgehampton, Connecticut and several locations in California, always a hot bed of racing developments.

The elements that inform our study of the sport in Michigan are these: National events led fairly quickly to the establishment of purpose built race courses that replicated open road conditions to the greatest extent feasible. The races at Watkins Glenn, Bridgehampton and Elkhart Lake all produced crowd control and safety issues that race promoters were, in the end, unable to overcome, just as earlier officials failed in the early 1900s. The death of a child spectator at Watkins Glenn in 1952 and injuries to spectators at Bridgehampton drove the sport towards closed courses.14 Public officials became increasingly reluctant to accept the possible financial liability and the certain political liability for mishaps.

Strong individuals led the effort to develop purpose built race courses. Cameron Argetsinger at Watkins Glenn and Cliff Tuft at Elkhart Lake15 have become legends of the re-born sport for their efforts. Limerock Park in Connecticut was born largely under the direction of now legendary race driver John Fitch, a star of all of the early days of post war road racing.

A most important bridge from the revived public road days to the era of purpose built road racing courses was provided by the United States Air Force. General Curtis Le May had taken a keen interest in "sports car" racing, as it was known, and also had a strong desire to promote and support interaction with civilian communities. With the blessing of the Eisenhower administration, General Le May saw to it that Air Force bases around the country were made available to be converted to temporary race tracks.16 They were, of course, flat and, by sophisticated racers' standards somewhat boring, but they provided a safe, controlled and politically safe way to hold the races (a program from the Janesville Wisconsin Airport races is included and discussed in this paper). Closer to the military connection, races were staged on the National Guard airfield in Grayling Michigan for many years and races were held at the Grand Rapids airport after operations were moved to the Gerald R. Ford airport serving the city today. The conversion of the old Grand Rapids Airport to an industrial park played a role in the founding of Grattan Raceway, one of the main subjects discussed below.17

Although it occurred after the events at Watkins Glenn and Bridgehampton, and after the move to airport courses, the crash into the grandstands of a Mercedes Benz sports racing car at LeMans in nineteen fifty five, which killed eighty eight spectators and injured many more, cemented the move to carefully controlled facilities and changed the face of the sport, even in the United States.18 The Automobile Club of America, founded in 189919 took the occasion to withdraw from its long time role as the lead sanctioning body of American racing. It was succeeded in stock car racing by the already ascendant NASCAR and in open wheel racing by USAC, the United States Autoracing Club.

Nostalgia for the "Golden Days" of American Road Racing has led in recent years to a surge in historical activity and writing. "Vintage" car racing has become a big business. Vintage cars are race cars at least twenty years old. Many are "restored" to better than new condition and are rolling museum pieces. At the top of the sport, money seems the primary moving force. Cars are routinely auctioned for amounts in excess of one million dollars. There is keen racing of cars in all vintages under this upper crust and both Gingerman and Grattan are the sites of popular vintage events each year. Although Waterford Hills has not tried to make a business of vintage racing for many years the track was the site of popular vintage races associated with the world famous Meadowbrook Concours D'Elegance.20

This brief history brings us most of the way to the point when we can turn to events in Michigan. Before doing so, we shall take some time to consider the literatures of the early days and also afford ourselves a carefully focused look into an event outside of Michigan that epitomizes the early days of reincarnated road racing. This last event, the races at Janesville Airport, Wisconsin, bring into sharp focus all of the specific and pertinent elements of the post war road racing experience.

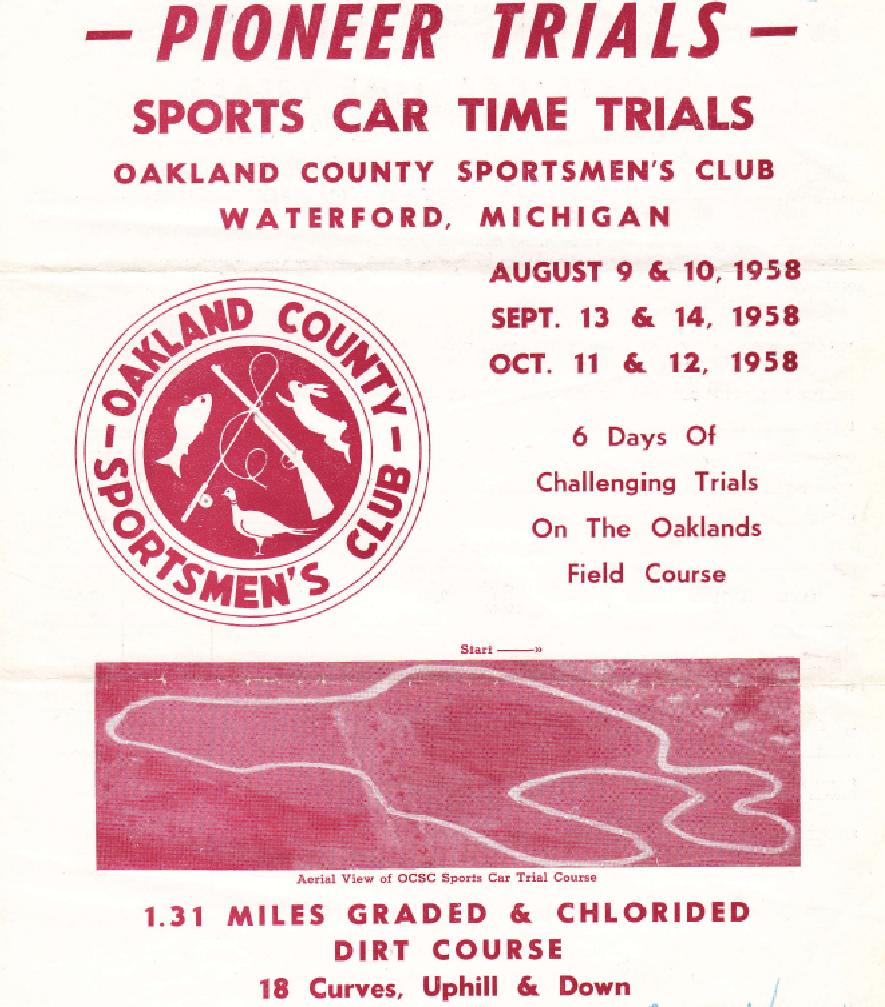

JANESVILLE AIRPORT

Although the Janesville Airport races of nineteen fifty two fall later in the history of road racing than the public road events, the program for these races illustrates most of the defining elements of post war amateur road racing. In this event we see the organizational infrastructure that is still employed today.

The races were sponsored by the Janesville Junior Chamber of Commerce, which was responsible for securing the dates and the facility, raising money, organizing and scheduling the events, providing for promotion and helping arrange volunteer services.

Advertising was sold, some to businesses with a direct interest in cars and racing, like Harder's21 and some who would benefit directly from the event, such as the Hotel Monterey22. More advertising was sold to prominent local businesses which would want to be seen supporting this community event. The naming of the races23 is entirely typical. The biggest donor/ buyer had to be the Parker Pen Company, whose presence and history in Janesville was and is a source of community pride. The list of entrants on page seven lists the most powerful and glamorous cars in the program and two of the drivers, Kimberly and Wacker were national figures in the sport. The Parker Pen Trophy Race would have been regarded by the racing crowd as the feature event of the weekend.

The weekend included a "Concours D'Elegance" event, a show for carefully restored cars which ordinarily would be judged by a panel of experts. The essay on the Concours includes a discussion of coach builders, businesses that would put a custom body on a chassis, a very different approach to manufacturing cars than the production efforts of the day. Kimberly's entry of one of his racing cars would not happen today.24 Neither would the inclusion of No. 210, a 1952 Jaguar with a Cadillac V-8 engine.25 Hybrids or "specials", as will be discussed below, would not be allowed. Cars that actually race would not meet the standards of perfection judges at today's events would require. Car shows, however, as opposed to pristine concours events, are a regular feature of road racing weekends even today. Waterford Hills has several groups per year showing off different brands of cars for spectators. The owners get to drive the cars around the race track during lunch and worker breaks.

The Program shows that even in this early day enthusiasts were interested in "vintage car" racing, cars that were too old to be competitive or too scarce to be risked in regular races or both.26 Even in nineteen fifty two, pre-war Bugattis, Mercedes Benz and Dusenbergs would have been too valuable to risk in the rough and tumble of a normal race.

Pages five through seven also show how the cars were divided up into classes, both as to size and type of car and the status of the driver. Most clubs and other racing bodies have followed SCCA classifications over the years. That way drivers could compete in local events but know they would qualify for SCCA events when they wished.

Page nine shows an aerial view of the airport with the track of the race superimposed. The layout provides for six corners, some sharper, and therefore slower, than others. Some come at the end of long, high speed straight-aways and others after shorter distances. The program also includes an essay by Jim Kimberly on airport racing. Kimberly addresses the safety issues and discusses the distinction between American and foreign attitudes.27 Within the limitations of using airport runways and taxiways, every effort was made to tax the acceleration and braking abilities of the cars and drivers as well as their cornering ability. The races would have been held in whatever weather conditions existed at race time, on the premise that if conditions were wet and dark those are the conditions in which road cars are driven. This is the essence of road racing in the post war period. Cars should be driven in the conditions they would encounter on public roads in every day driving and drivers should have the skills to match.

Purpose built racecourses would add many more turns of greater variety and would incorporate elevation changes, which is to say, hills, whenever possible. One of the most famous turns on a road racing track is the "corkscrew" at Laguna Seca Raceway in California, which turns 90 degrees left and then 90 degrees right, going sharply downhill the whole way. One might have to drive in San Francisco to experience this in "real life", but its contrast with four flat identical corners at Indianapolis will be appreciated.

Returning to Janesville, it can be seen in this picture how airport races were an improvement over public road races in terms of crowd control and safety. An airport is a controlled facility to begin with: there are fences and gates. And the well defined, clearly visible corners are easily observed. Race control could probably see the entire track from the start - finish line. It would take a very sophisticated design approach after many years of racing experience to duplicate these features at such tracks as Gingerman Raceway.

Road racing was often in the early days referred to as sports car racing, and for a long time afterward. The Janesville Airport program provides us with a crystal clear picture of what was meant by a "sports car" and the distinction from other, mostly American cars.

After the War, Americans went for power, comfort and convenience in cars as in many things. Power output increased dramatically, as did gasoline consumption. But gasoline was cheap and plentiful, unlike the conditions in Europe. The automatic transmission became widely available, as did power brakes and steering. The cars became large, with large cargo compartments (the "trunk") and plush interiors. Suspensions, the infrastructure that connects the wheels to the rest of the car, were engineered so as to provide the smoothest, most comfortable ride. In response, many public roads were engineered to accommodate leisurely steering and braking. The results of all this were cars that were not suited to performance driving, as noted by Phil Stiles in What is a Sports Car?28

Some cars manufactured in the period between the two world wars were respected by "sports car" people. Griffith Borgeson in The Golden age of the American Racing Car presents a wonderful history of what he and many regard as the golden days of American Racing cars. Out of this heritage came many of the early SCCA members and the members of ARCA. But in the post war era, that all changed. Featured early in the Janesville Program, the essay "What is a Sports Car?" drips with the disdain early road racing aficionados had for the typical American automobile.29

Between sarcastic references to American cars, the author gives a fairly realistic account of the difference between the average American car and the sports car, read "imported European "car. For those who don't quite get it, the author lays out the differences between road racing and oval track racing under the heading "There's a Difference".30 This is the most bombastic section of the essay; actually many oval track racers drove road races and were wonderfully competitive. Many more have done so since. The great A. J. Foyt won the LeMans twenty four hour race partnered with the sports car racer Dan Gurney. And Gurney competed successfully at Indianapolis as a driver, a car designer and a car owner. Indianapolis drivers and NASCAR drivers have proven on many occasions that a good race driver is a good race driver, period. But in 1952, the differences were perceived as large.

It should not go unsaid that the author's final point was true then, all the time since and true now. Sports cars were and are more fun to drive. "Sports cars" were European cars smaller, more maneuverable and, with some eccentricities, better performers in steering, braking and road holding. They were also tougher in the sense of handling hard driving better, although not necessarily as reliable as American cars. Burt Levy's fictional hero Buddy Palumbo breaks into sports car racing fixing Jaguars and MGs that are more temperamental than the average American car. But when they ran, they delivered a kind of performance American cars could not match.

The later essay in the program, "Why Drive a Sports Car?" elaborates on the case begun in "What is a Sports Car?"31 It was true that the cars could be safely driven at one hundred miles per hour and as noted above, that some competitors drove their cars to the tracks, emptied their personal property and raced the cars. That is occasionally still done. Note also the comparison to European racing, regarded as more sophisticated and glamorous than the average dusty local American circle.

The reference to the No. 1, Kip Stevens Excalibur, and the No. 210 Jaguar-Cadillac noted above highlight an important facet of road racing: the building of "specials". Specials were purpose built race cars designed, engineered and built by owners. Some were relatively simple applications of technology from one car to another. The Jaguar Cadillac is a good example. This hybrid capitalized on the Jaguar's superior road holding and the Cadillac's greater power. Others may have used some production car components, but would have been very substantially custom crafted.

Specials have a long tradition in road racing. John C. Rueter, author of American Road Racing, built "The J. Rueter Ford Special was designed and built by Lemuel Ladd of Boston's Oak Hill Garage, and myself. It was made up of parts from nineteen different makes of cars"32 Specials had their heyday in the late 1950s and early 1960s in SCCA racing. This tradition reached its ultimate form in the AC Cobras constructed of Ford V-8s and British AC Ace chassis and the Scarabs of Lance Reventlow and the Chaparrals of Jim Hall. The Cobras, developed by legendary road racer Carroll Shelby, eventually went into limited production and so crossed out of the Special category. Reventlow's Scarabs and Hall's Chaparrals were custom fabricated by these wealthy individuals and took on the elite of top line foreign competition. All three cars moved into the professional world, although Cobras were sold to amateurs who raced them in SCCA races. But back in the early days many were produced from limited resources by amateurs hoping to improve their chances in competition.33Burt Levy's book The Fabulous Trashwagon is an entertaining look at this phenomenon in the early days of the renaissance.34

The short section on the SCCA only hints at several important elements of the renaissance period.35The first sentence uses the word "amateur" and blood battles were fought in the SCCA over its idea of amateurism and its sole status as arbiter of that question.

The reference to ARCA borders on hypocrisy. The SCCA did benefit from some ARCA members, but the SCCA's roots were more in the Concours set. Notice that the words "driving" and motoring were used more often than "racing" in this piece. Racing was approved only when the ruling class in the SCCA was overrun and then they made every effort to exert complete control. The SCCA actively worked to undermine the efforts of many early race developers and promoters where it could not get control. The participation of SCCA members is "intelligent and disciplined" and attracts the attention of "responsible civic and automotive engineering bodies". The SCCA's "unremitting efforts" have raised the status of the automobile from that comparable to "an ice box...or some other routine accessory whose prime purpose is...utility".

The upper class tone is no accident and is not imagined. As noted elsewhere, the SCCA's roots are with the collector class. Prior to Cameron Argetsinger's promotion of racing at Watkins Glenn, SCCA events consisted of taking trips in their cars and showing them off. Among its many painful early episodes, the Club waged a long struggle against the participation of Erwin Goldschmidt, the son of a wealthy Jewish banking family that fled Nazi Germany just before the war.36 Goldschmidt, by Michael Argetsinger's account was a "confident and forceful" competitor who could afford the best cars. His brashness made him an easy target. Although highly educated, he was denied membership in the SCCA and was allowed into the 1950 race only because it had been granted international status by the FIA, the international sponsor of races in Europe and elsewhere. That status was resisted by the SCCA for fear of contamination by professionalism and for fear of the SCCA's loss of control. Goldschmidt was allowed in because of an affiliation with another FIA recognized group. The SCCA, the official manager of the race, made Goldschmidt's life miserable. The final indignity was being made to start last, behind many slower cars. Argetsinger says he passed twenty cars on the first lap and eventually won the race.

Goldschmidt may have been the model for Big Ed Baumstein, the cigar chomping, womanizing Jewish junkyard owner who is the main patron of Buddy Palumbo's participation in sports car racing in the series of books beginning with The Last Open Road.37 Author Levy effectively lampoons the behavior of early SCCA snobs as they deal with Baumstein's repeated attempts to join in the events. Argetsinger says "The SCCA was not anti-Semitic by policy or design. The anti-Jewish feeling among some members was more a reflection of the general prejudices shared by many people at the time."38

Argetsinger's commentary, Levy's well informed fictional account and other sources indicate that when the SCCA "sponsored" an event, it was to by run their way without much regard for the wishes of the local promoters. The Janesville Jaycees, promoting an event to benefit their community, would have received very careful, detailed and definite instruction on the conduct of the event.

A final notable element of the road racing experience on display at the Janesville Airport races was the service of many volunteers on the track. Road racing depended on volunteers for safety and communication services and does so to this day. On track communication, safety services and timing and scoring at the recent professional races on Belle Isle in Detroit were staffed almost entirely by volunteers recruited from Michigan Turn Marshalls, a cadre of workers, many of whom are from Waterford Hills and the Detroit Region of the SCCA.

The use of flags is discussed on page twenty three, as is the role of the starters and the flag marshals stationed at every corner on the track. This flag system is almost exactly what is employed today at all SCCA events, most international events and at most club tracks around the country. Flaggers, as we are most commonly known (the author participates at this level), are part of the racing and are often at as much or more risk than the drivers. Waterford Hills has suffered only two fatalities in fifty years of racing, a driver who may have had a heart attack and crashed as a result, and a flagger who was struck by a car gone out of control. Page twenty two discusses the services of a shortwave radio club that provided on course communication for the Janesville races. Although probably not a major problem at Janesville, at most road courses the race control group cannot see the entire course. Appropriate flag conditions, the dispatch of emergency vehicles and other control issues must be communicated from the corners. In the early days this was a serious problem that multiplied the risks for all participants. Today the corner workers have radios or dedicated land line systems that bring instant information to race management. In nineteen fifty two, at Janesville Airport, Lowell Wilson supplied that need out of the trunk of his new Studebaker.39

As seen throughout the program, the races were sponsored by the Janesville Junior Chamber of Commerce, which was responsible for securing the dates and the facility, raising money, organizing and scheduling the events, providing for promotion and helping arrange volunteer services. This kind of local civic "boosterism" was critical to the development and survival of the sport in the early years, and some think to the general well being of the country. The history of service organizations like this is surely worthy of study in and of itself. The Janesville Jaycees still exists, but does nothing on the scale of producing these races and it is probable few such organizations do anything like this today. The social and cultural forces that made the Jaycees what they were are gone, probably victims of television, big scale commercialism and the cynical "sophistication" that came in the 1960s. Corporate sponsorship in the amateur sport today is confined by rule to equipment for individual cars and is tightly regulated. It is unknown whether any major businesses would support an amateur event today. It is clear that many local businesses took great pride in supporting that event back in nineteen fifty two.

What may be read as the cheerful goodwill, sunny optimism and even the brash but good natured certainty of the special value of sports car road racing still exists in some small spots today here in Michigan. All of the elements we saw in our general history of the renaissance of the sport and at Janesville Airport came into play as the sport developed here and we will now turn to that story.

GRATTAN RACEWAY

Most knowledgeable fans will say that road racing was born in the late nineteen forties and grew with the American prosperity throughout the nineteen fifties and into the nineteen sixties. Many consider those the golden years of the sport. Numerous histories and Burt Levy's well received novels celebrate that time. It was a time of social and sports clubs and service clubs and community booster-ism, as we saw at Janesville Airport. And a time of great expansion in participation in sports by the American middle class. As predicted by Billy Durant in his last wave of entrepreneurial insight bowling became a popular family sport and it did so40, a fact of some minor coincidence in the story of Grattan. It was a time of nuclear families, a renewed celebration of male family and cultural leadership and an explosion in small business. If you have the good fortune to know the Faasen family, a trip to Grattan Raceway, especially to attend a vintage race meet is as close to being in that golden time as one can imagine. (Illustration 1)

A ride on two lane country roads brings you to Grattan Raceway. The rolling countryside is dotted with lakes and camps, with a few new upscale housing projects but also small, old cottages. Much of the land in the area is farmed and it is easy to imagine you are in upstate New York, on your way to Watkins Glenn.

The track is located in rural Grattan Township, twenty five miles north-east of Grand Rapids and occupies a picturesque site. It is surrounded with old growth forest and two lakes and contains some evergreens left over from the Christmas tree farm that occupied the property before the track. The Faasen family that owns and operates the track has fished and hunted on the property since the earliest days. The ponds inside the track are stocked with fish. Many race events are family affairs and children may be seen fishing between and after races. (Illustration 2)

The track itself is reached by a narrow country road, an uphill right turn just before you enter the hamlet known locally as Grattan. "Grattan" is properly the Township, but most people who patronize the track mean the hamlet and the track when they say the name. The hamlet consists of a few houses, a party store and the Grattan Tavern where on race weekend nights the crowds gather to eat bar food, drink beer and tell racing stories. Grattan takes one back to the early days of road racing in every way imaginable, back to the nineteen fifties. Driving in, one would not be surprised to see old MGs and Jaguars and on vintage racing weekends you do.

Edward Jack "E. J." Faasen is a businessman in the best sense and tradition of American small business and has been all of his life. At the center of the story of Grattan Raceway is the story of a small business coming out of the nineteen fifties and nineteen sixties in the United States, the story of a family business. E. J. and Mary Faasen's home, atop the main building at Grattan Raceway and his office are decorated with pictures of family, family outings and family events. Grattan Raceway is first and foremost a family business and E. J. Faasen is the patriarch.

E.J. Faasen is seventy seven years old now - his age is mentioned twice in the small collection of newspaper clippings he has saved - and details of some events change with second and third telling. But the essentials of the founding and early days of the track are consistent between the newspaper clippings and the telling.

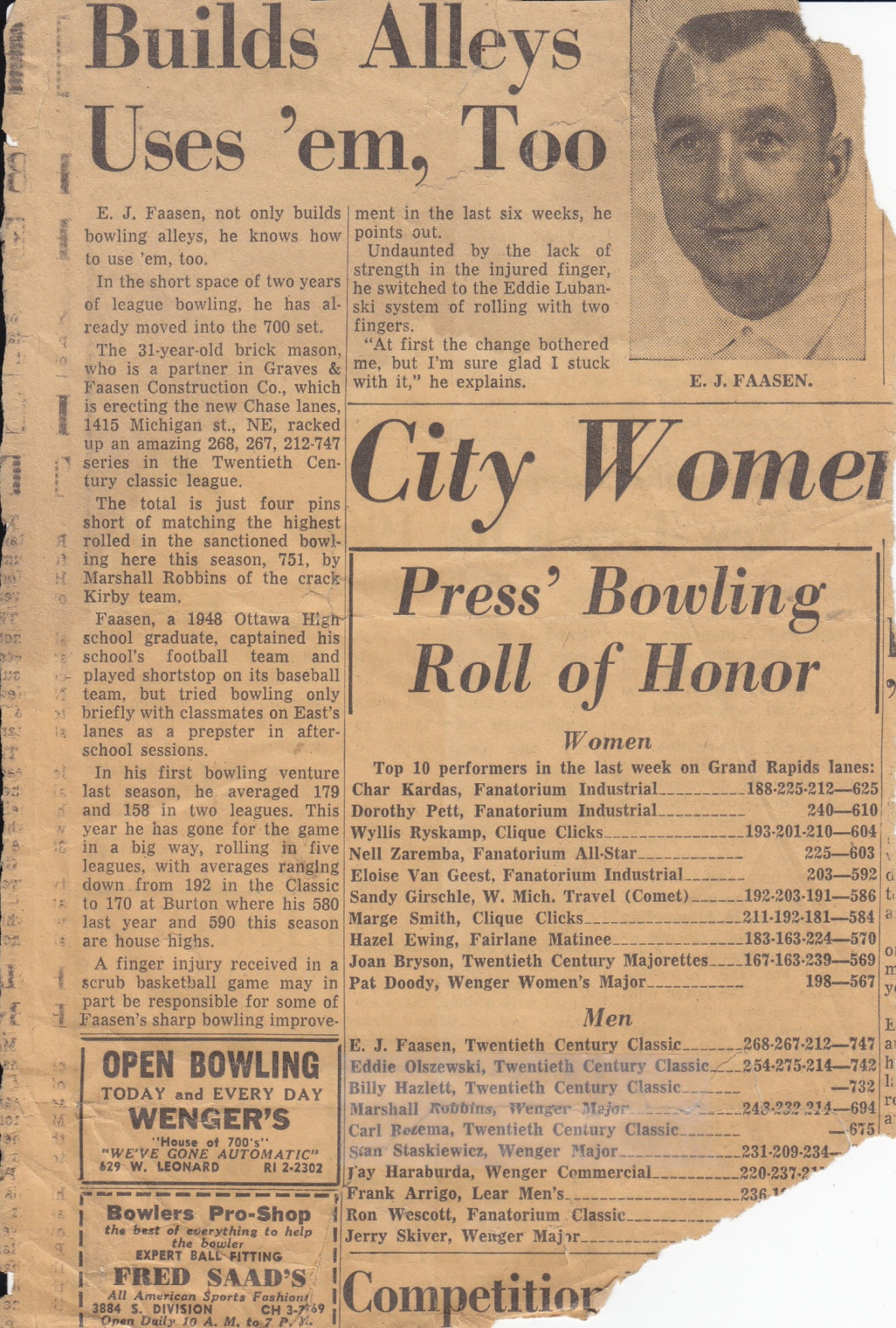

E.J. started as a masonry contractor. He did a lot of commercial work in Michigan and in Florida, where he built housing on Patrick Air Force Base near Cape Canaveral. He made many acquaintances in business and became something of a notable sportsman himself. He built several bowling alleys in the Grand Rapids area, got hooked by the sport and became Grand Rapids City champion. The first of several newspaper appearances records this early sporting career. (Illustration 3)

E.J. Faasen did not set out to be in the racing business. Eugene Christenson was a used car salesman and a partner with E. J. in some business projects. Christenson was interested in sports car racing and once took Faasen to the sports car races at the Air National Guard airfield in Grayling, Michigan. Bill Tuttle, another mutual friend, owned a property, a tree and flower farm known as the Lessiter Farm on what later became known as Lessiter Road in Grattan Township. A group of sports car people urged the construction of a racetrack on the property and agreed to contribute funds. Tuttle would contribute the property. When the time came to ante up, Faasen had cash and construction experience and Tuttle had the property. The others had only their enthusiasm so Faasen and Tuttle became partners.

The track opened as a business in nineteen sixty two.41 An article from the Grand Rapids Press dated May 13, 1962 reports that "International Acres Raceway" in Grattan Township was nearly complete with a three thousand foot drag strip.42 The article notes that a road course was either in place or contemplated and the hope was to have the road course paved by July of that year. The May 1962 article said the facility occupied one hundred and forty acres and that E.J. Faasen was President and Bill Tuttle, Vice President. E.J. Faasen is quoted as saying there was an option to purchase eighty acres adjacent to the site.

Faasen says he and his wife mortgaged their house to get the money to pave the drag strip. At some point early in the business years Faasen bought out the interest of Tuttle and became sole owner. Faasen has said that having money in the project, he had to take an ever greater role to just to preserve his investment. It became a life- long occupation and the center of family life.

E.J. and Mary Faasen had nine children, which was at not unusual for families in the nineteen fifties. All of the children worked at the track at some time. Faasen's mother worked in the concession stand in the early days of the track and grandchildren have worked there in recent years. Mary worked in the concession stand in the early days and in later years became the business's bookkeeper. E.J. remembers son Kurt at twelve years old being the announcer for the drag races. Thus the family ran the drag strip on Saturday and did maintenance the rest of the week. They published a newsletter with an old hand cranked mimeograph machine. To make ends meet E. J. worked part time jobs, teaching architectural drafting at a local trade school.

Drag racing was still being conducted at Grattan as late as 197343, but probably not long after that. Drag racing outgrew Grattan. The cars became so fast that the track did not have a long enough "run off" area where the cars could slow down and they had no room to expand it. (Today top cars reach speeds of over 300 miles per hour in their one quarter mile acceleration.) E.J. says the National Hot Rod Association, the professional sanctioning body of the sport, decided not to come back after a car was unable to stop, ran off the property and ended up in a corn field across Lessiter Road.44

Almost from the beginning E.J. was expanding the business horizons of the Raceway. The track has been rented to professional driving schools and police departments began using the track as early as nineteen seventy eight45 for high performance drivers training and still do. The straight away was used as a runway by a skydiving club until the plane crashed just off the Faasen property, tragically killing all on board.46 The track has been used for bicycle racing and has been rented to professional racing teams practicing for events as varied as the Detroit Grand Prix and the Indianapolis 500.47 In the late nineteen sixties, as the new sport of snowmobiling was beginning, E.J. proposed a snowmobile park to capitalize on the track's setting and produce some extra income. He was primarily a racing promoter, but sports writer Alex Laggis characterized him as "…a man who would rather switch than starve…"48 But road racing, in various forms, quickly became the mainstay.

Some people remember the road course as a gravel track that left one end of the drag strip and rejoined at the other end.49 Faasen has said more than once the layout of the road course involved a jeep, a few drinks and a desire to make maximum use of the property. He also told me he took a big vodka and orange juice, got in the jeep, turned right off the end of the drag strip and made a turn wherever there was a tree too big to run over with the jeep.50 Other stories indicate it was a couple of people and a few beers. Memories seem equally hazy on exactly when it was paved.

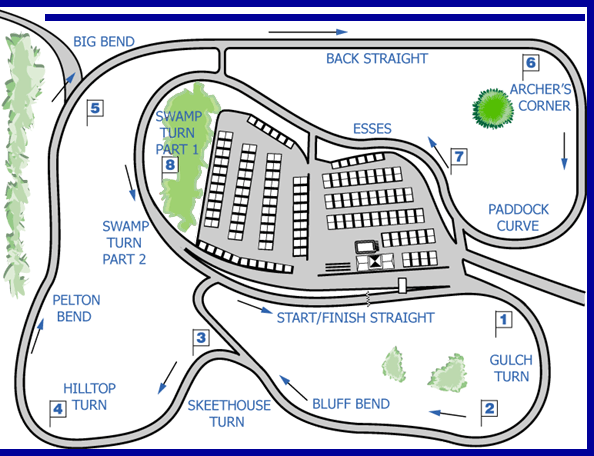

However the layout was achieved, it is very different from tracks built in recent years. This track is long as road racing tracks go today, twisting up and down hills in what appears a random fashion and features a "ski jump" where some cars leave the ground altogether. There is little of the steel Armco barrier that completely surrounds "modern" tracks. New tracks are almost invariably "technical" tracks, with turns of carefully designed radius engineered to provide a test of chassis design and tuning. Turns follow one another on a carefully designed agenda so as to reward precise placement of the car at various points in a lap. Technical analysis and the related style of track management produce wins at many tracks. Grattan is a track that rewards brave, imaginative drivers and powerful cars. The inclusion of the former drag strip gives Grattan one of the longest straight-aways of active tracks. At a recent SCCA event one of the faster cars was clocked at nearly one hundred ninety miles per hour on the straight-away. That flat, smooth straight-away ends, however, with a sharp right hand turn onto asphalt followed by another sharp right hand turn followed by a sharp left hand "negative camber" turn. That is, the track goes sharply downhill just as it turns and the outside of the turn is also the downhill side. Drivers must fight to keep the car from sliding off the track and down the grassy hillside into one of the ponds. Subsequent corners go up and down hill and there is almost no straight track until the car comes back to the front straight-away. Whether the design is serendipitous or crafty, it is a layout that calls for skill, courage and offers drivers many options in strategy for managing their race. Grattan offers more speed than either Gingerman or Waterford and that alone would make it a favorite with most drivers. (Illustration 4)

The 2009 season schedule is a roster of most of the clientele that has been important over the years to Grattan and fairly outlines the many forms road racing has assumed here and throughout the United States. Gingerman pursues the same clientele, but with more focus on testing and development rentals. At Grattan there are twenty four motorcycle events scheduled between March 29 and October 19, nine car club events, four sports car racing events, two scheduled "car track" days and two open dates. All of the sports car events and many of the motorcycle events will be multiple day events, usually Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

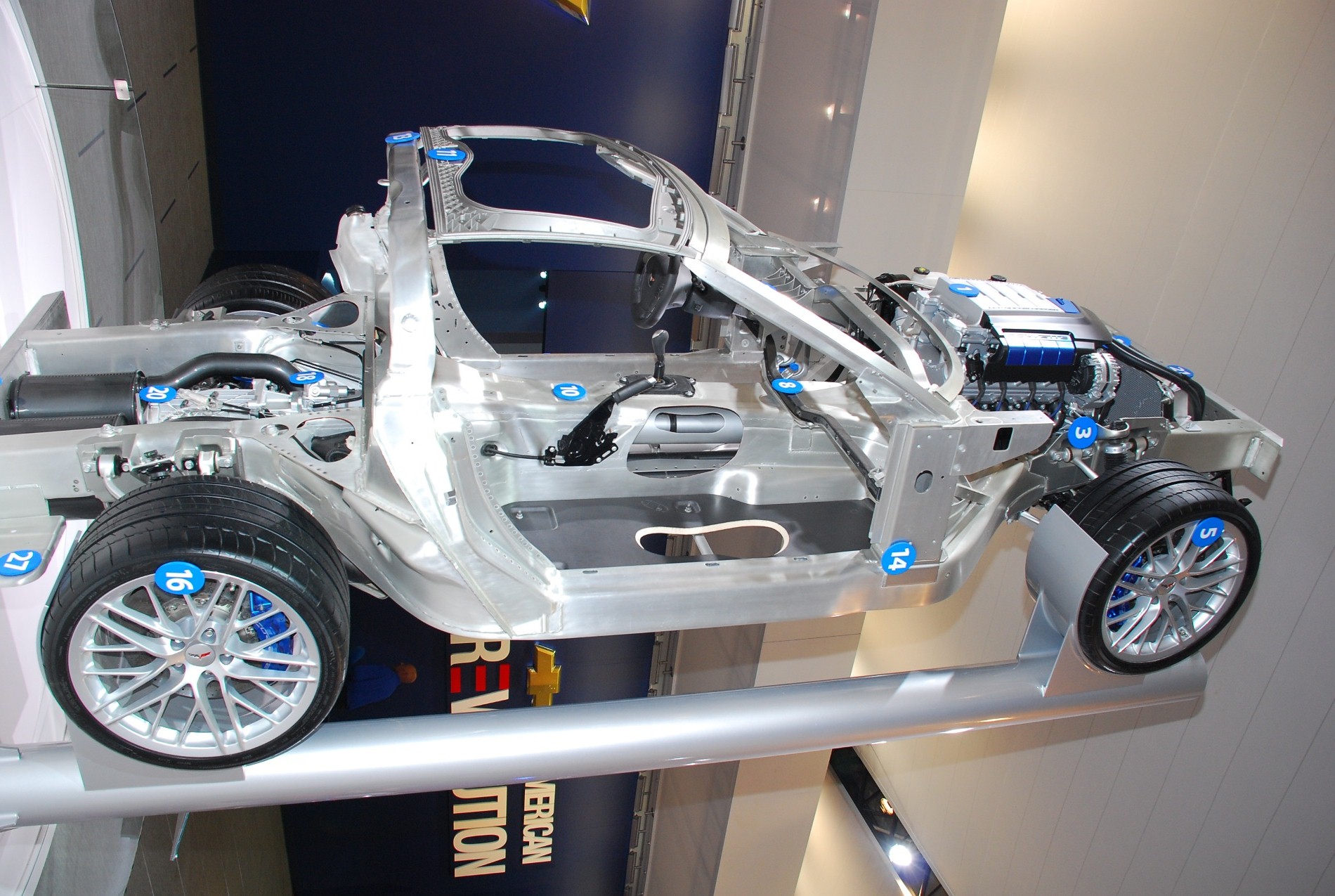

The car clubs remind one of the sport's foreign roots. All but one are clubs for owners of foreign cars and the one is a Corvette club. The Corvette was General Motors answer to the foreign sports car invasion in 1953 and it is still in production. The foreign cars represented include most of the royalty in foreign cars. Audi is a German manufacturer whose predecessor was the pre-war racing powerhouse, Auto Union. The Company's logo, four interlocking rings, symbolized the union of the four companies that joined to create Auto Union. Alfa Romeo is a great old Italian name. The company was the training ground in design, production and racing for Enzo Ferrari who became famous producing and racing the cars bearing his name. Porsche is another famous German name, whose original design was a variation on the Volkswagen, a car engineered and designed by Dr. Porsche at Adolph Hitler's direction in pre war Germany. Although Volkswagen, as it is spelled today, is not usually considered a sports car, the brand has many driving enthusiasts and that club will be at Grattan in April. BMW, formerly Bayerische Moter Werks, another German name, is thought of as primarily a post war company. It is mostly known for high performance sedans, although it has started building two seat sports cars in recent years. Lotus was a truly elite British manufacturer of racing cars that eventually entered limited production of sports cars for the road as a means of providing resources to support racing operations. In this it resembled Ferrari, the great Italian manufacturer and Lotus' primary competitor in the highest level of the sport, Formula One. Lotus effectively died with its genius founder, Colin Chapman. The name has been revived in recent years, but by Indian and Japanese interests. Ferrari and Mercedes Benz are the only great foreign names not to have a day at Grattan.

The clubs generally have carefully organized practice sessions and then competitive time trials where cars circulate one at a time as fast as they dare. Club days, as well as car test days provide the opportunity to test the limits of insurance coverage. There are stories of damages not claimed on insurance and repaired out of pocket and one story of a man who totaled his wife's Porsche, who did not know he had taken it to club day. Trophies are awarded at the end of the day and, if desired, the day ends with a dinner catered by the Faasen's.

Motorcycles have figured prominently in Grattan's success from the earliest days and E. J. Faasen says he could lose all of the other events and still make a little money if he kept the motorcycles. There are forty three days of motorcycle events, split between two very different approaches to the motorcycle sport.

District 14 of the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) sponsors the motocross events held at Grattan.51 The District's website says motocross is the most popular form of amateur motorcycle racing and describes motocross as "…races…run over closed courses utilizing natural terrain and some man- made obstacles to test rider's skills and speed". The courses are unpaved, usually becoming rutted, are usually short and feature hills that launch motorcycle and rider high into the air. The motorcycles used in motocross are of simple rugged construction and are engineered for durability in extreme use. The"moto" track occupies hilly ground across the service road from the road racing course, the additional property acquired after the drag strip opened. It has proved to be a valuable addition to the racing plant at Grattan. It's separation from the main track makes it possible for the Faasen's to host two events on the same day or days.

Western Eastern Racing Association (WERA) is a non- profit organization formed in 1973 for the sole purpose of sponsoring and promoting motorcycle road racing.52 WERA is a nation- wide organization today, operating independently of the AMA and other organizations. WERA sets rules and designates classes and sanctions and operates events. Like the SCCA in automobile road racing, WERA's sanction assures entrants of uniform rules and fair competition.

As with automobiles, Grattan hosts once a year a vintage event for motorcycles. The American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association (AHRMA) holds a two day event, usual y mid-year.53 The American Historic Motorcycle Association, Ltd. is a not -for-profit organization dedicated to restoring and competing on classic motorcycles." Formed in nineteen eighty nine, AHRMA grew out of a loose association of regional groups. In addition to races, the events typically include a concours event where owners show off classic motorcycles that have been restored to at least new condition, if not better than new.

There are three entities holding motorcycle events at Grattan which appear to be for profit ventures. The schedule lists several S.B.T.T. Open Track Days. The Sport Bike Track Time organization organizes and operates days where nearly anyone owning a motorcycle can register, show up at the track and drive his motorcycle around the track at speeds not possible - not legal - on public highways.54 These are not racing events; there are rules regarding passing, separation on the track and other restrictions designed to promote a modicum of safety.

Apex 2 Apex is owned by two WERA professional motorcycle racers and organizes open track days similar to those conducted by SBBT.55 The Apex 2 Apex website notes there events feature "a less crowded track" and more track time. The Team Chicago Motorcycle School is put on by a Chicago based motorcycle entrepreneur who owns a cable television show in the Chicago market devoted to motorcycle activities.56

There is one go kart event listed for two thousand nine. Go karts used to be tiny, open four wheel vehicles often powered by a small lawn mower type engine. The sport has become so popular in recent years that there are indoor facilities located in major metropolitan areas. The group racing at Grattan is an "enduro" (short for endurance) series, holding races that are long in time and distance compared to other races. These groups race vehicles that are tiny, but are often powered by more sophisticated engines and have transmissions. These karts will reach speeds in excess of 100 miles per hour and often race at large tracks like Grattan.

Sports car races are of two types. Three are SCCA races, sponsored by various SCCA regions and one is the Vintage Sports Car Drivers Association "Sprint Races"."Vintage Racing" - racing cars older than twenty years - seems lately to rival racing current sports cars in the number of cars participating and in events held. Several organizations devoted to sanctioning and staging races have sprung up. The Vintage Sports Car Drivers Association (VSCDA) is a non- profit organization with about eight hundred members. 57 This segment of the sport is chronicled by several magazines and is featured in broadcasts on television.

As it has with other racing venues and personalities, the SCCA has had a long but occasionally tempestuous relationship with Grattan Raceway and E. J. Faasen. A newspaper story dated in 1970 discusses an SCCA national that race was closed to spectators after a dispute over who would pay for insurance against claims by injured spectators. Faasen said it would cost about $4,400, money he could not afford to pay.58 Another early newspaper clipping recounts a dispute over money in which the SCCA official involved is quoted as saying that Western Division members worked on the facilities with the understanding that they were paying in advance some of the cost of using the facility in the future. Charges and countercharges flew, but eventually, the SCCA came back to Grattan.59 On another occasion a prominent SCCA member gassed up his car and started to drive away. When he was stopped by one of the sons, he asserted that the SCCA didn't pay for gasoline, that gasoline was always part of the package. When told about that, E.J. parked a large construction truck across the track, locked it and told the SCCA officials when they were willing to pay for gasoline they could hold a racing event. The SCCA started paying for gasoline.60

E.J. Faasen has exercised his right of eminent domain for the benefit of others on occasion. This past year, a vintage racer died at Grattan. His car simply went off the end of the straightaway without any sign of an attempt to slow or stop. The driver, a man in his sixties, had been only recently been cleared after heart surgery to return to racing. He was dead when the corner workers reached the car and it was later determined he had suffered a heart attack. The man's family was with him - his son, driving in the same race, saw him go off the track. When the local press arrived with a camera truck E.J. blocked the entrance to the track until the family was ready to leave. The car had been moved and there was nothing to see by the time the press was admitted. Dignified reports appeared later in the newspapers.61

Grattan is still a family business. Son Kurt lives on the grounds, upstairs from the registration building at the entrance to the property and son Sam lives just down Lessiter road. Sam schedules events. Kurt runs the food service. Grattan is famous among Midwestern road racing people for the Saturday night "pig roasts", where the food is plentiful and a keg of beer is always on tap. Commentary on Grattan on the Western Michigan SCCA website enthuses "At every SCCA race there is a dinner provided free to all workers, competitors and crew. It is one of the best in CenDiv (the central division of the SCCA). No half cooked brats or warm beer. It usually consists of chicken, beef, and pork, sauerkraut with sausage, meatballs, fresh rolls, baked potatoes, potato salad, macaroni salad, Cole slaw, corn, beer, pop and wine coolers. If you leave hungry, it's your own fault. AND IT'S FREE!!!!" 62 Actually, it is priced into the weekend. Daughter Terri runs the food concession during events where breakfast and lunch is available for moderate prices. Sons Max and Donald have worked at the track part time during events and Mary still helps with the business affairs and everyone helps with maintenance as needed. Grand children help in the concessions when visiting during an event. E.J. often cuts grass on the property during the week and the Western Michigan website says the property is sometimes mistaken for a golf course. (Illustration 5)

One of the most remarkable features of a road racing event is the establishment of what can only be described as a small city on race weekends. Thursday night the property is empty. By race day the city has been erected and populated, brought in on and in motor homes, trailers, semi tractor trailer combinations and campers. There are centers of commerce. Vendors set up selling tires, tools, spare parts, books and memorabilia, photographic services and art works. There are mobile machine shops and welders.

The "government" of the racing activity has its locations. Timing and scoring (those who keep track of the results), fire, medical and emergency services and race control all occupy their own places. Race control occupies the top of the tower, the city's skyscraper and it is the nerve center of activity during the races. From here on race day the gypsy band of corner works disperses to all of the corners of the track, to be first responders to cars in trouble and to report conditions to race control over the communications system.

There are neighborhoods in the city. The Formula 500 drivers "pit" together, as do the Mazda Miata drivers and the other classes of cars. Tools and advice are shared; sometimes engines and tires. Wives and children have become friends and in time weddings and funerals and graduations are attended away from race weekends. The competition on the track is real; so is the camaraderie off the track real and at Grattan the Faasen family pig roast is a warm highlight of the weekend.

But this city only exists for two or three days and by Sunday night the property is empty again. Grattan Raceway returns to its bucolic state. The Faasen family contemplates the work to be done in the coming week and retires to their home. (Illustration 5) Speaking to the writer about all those who come, live out the dramas of racing and then go, E.J. Faasen stands on the deck looking over his estate, as close to wistful, one thinks, as he gets and says "I enjoy them while they're here. I miss them some when they're gone." (Illustration 6)Then his face cleared and he shook my hand and guided me to the door. Grattan's story had been shared, on E.J. Faasen's terms, but now, like all the others, it was time for me to go.

Entrusting me with the small envelope of clippings that is all the official, public history of Grattan, E.J. said he would be at the track until January first and then will be in Florida until the end of March. Family members will join him and Mary in Florida at different times for fishing on the family's boat and relaxing away from winter.

E.J. Faasen honored the author and his wife to a brief visit to his home to show us his proudest achievement: a picture over the mantel of the fireplace of himself, Mary, his eight children and numerous grandchildren. Driving out of the property the thought occurred that the family will probably gather for Christmas in this beautiful place. Looking back, all that was evident on a cold winter day was the cluster of workmanlike buildings in the middle of the track, a self contained racing "plant" like, say, Daytona International Raceway. Then another realization followed: there is nobody's home in the middle of Daytona.

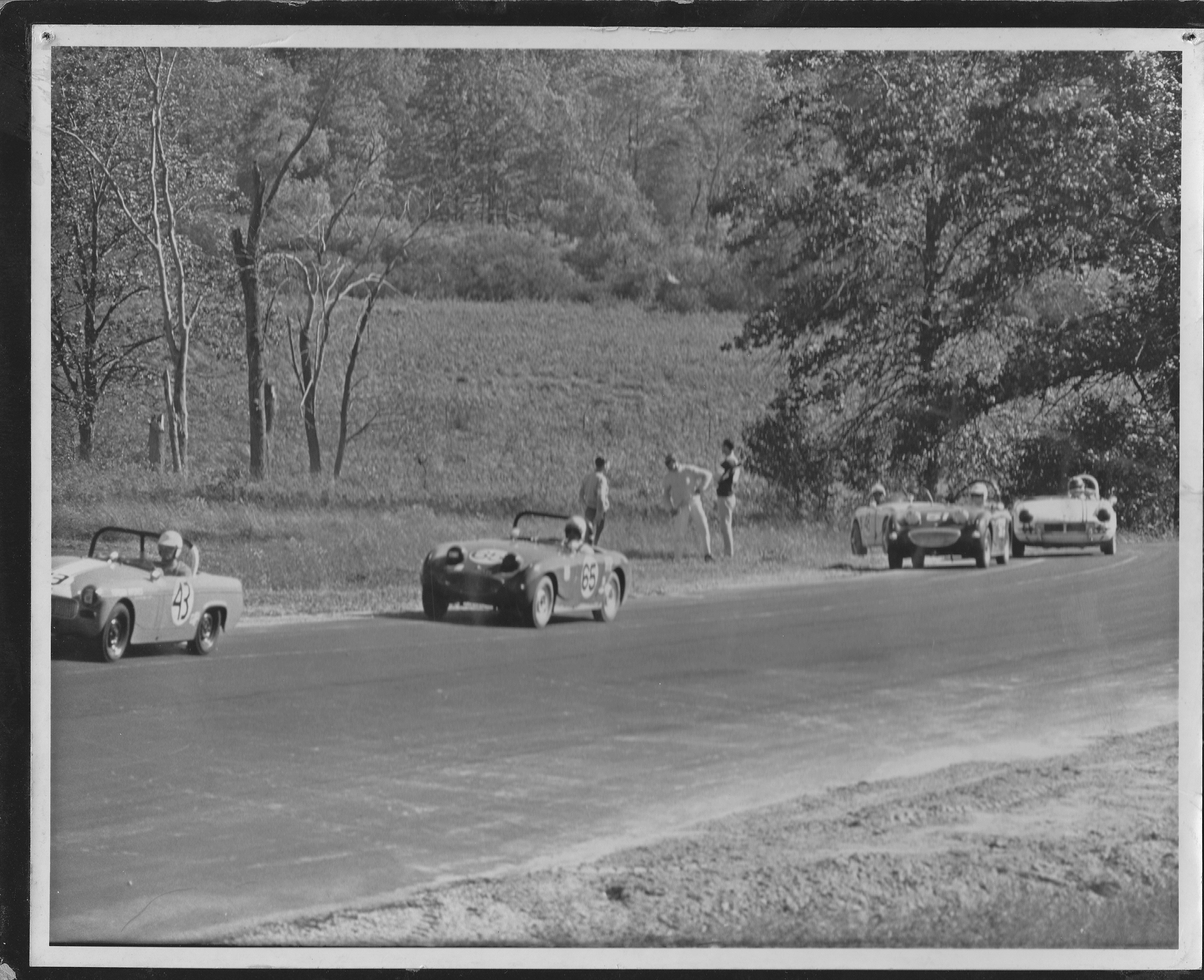

Illustration 1 This undated picture has to be from the earliest days of road racing at the track, probably about 1962 or 1963. Note the lack of barriers of any kind. Note also how close the corner workers are to the edge of the track and the lack of any kind of protective structure for them. Grattan has added small strips of steel "Armco" railings mounted on wood posts at the corners, but at Grattan, with speeds approaching 200 miles per hour at some events, close attention, good reactions and fast feet are still the corner workers' best safety equipment.

The picture shows how road racing circuits did indeed provide the experience of driving fast cars on country roads. The cars pictured here would all race as vintage cars today.

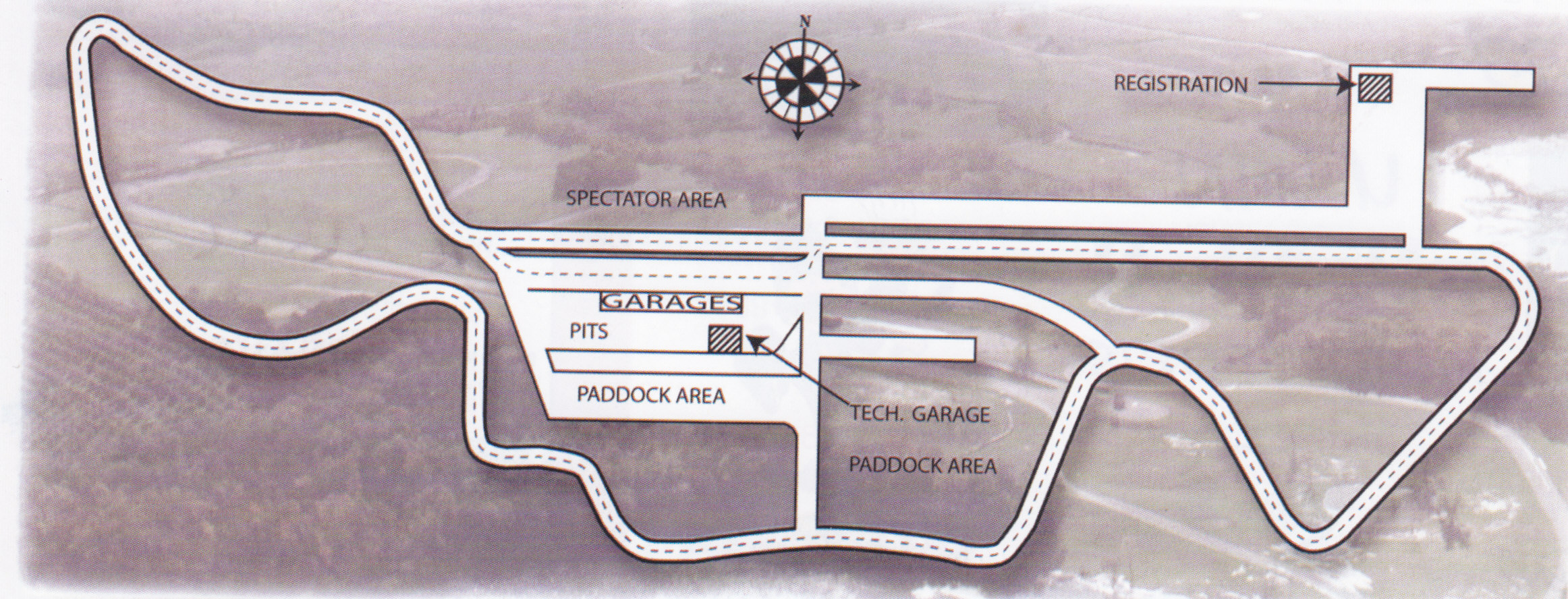

Illustration 2 Grattan Raceway from the Air

Lessiter Road and the entrance to the track are at the top right of the picture. Except for the asphalt surface in the pits, the dark patches are ponds inside the track and a lake in the upper left. E.J. and Mary Faasen's house is at the right end of the asphalt pit surface, looking out over a pond with an island in the middle where cars are pitted during really busy race events. The motorcycle "moto" facility is across the track from the asphalt pit area. At the left end of the long main straightaway is a semi- circular turn around area used to stage cars when the track was used as a drag strip. Upon close inspection white "dots" may be seen near each corner. These are small structures that "shelter" corner workers during races.

Like most racing facilities today, Grattan is subject to sound restrictions despite its rural location. Race officials are designated to monitor the loudness of the racecars. Grattan has had good relations with the Township government and most of the area residents. The Faasen's have often held Halloween parties for area residents. The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, an agency that did not exist when Grattan was founded, has never had a complaint with any of the activities at Grattan.

Promotional Brochure, Grattan Raceway, un-attributed photograph.

Illustration 3

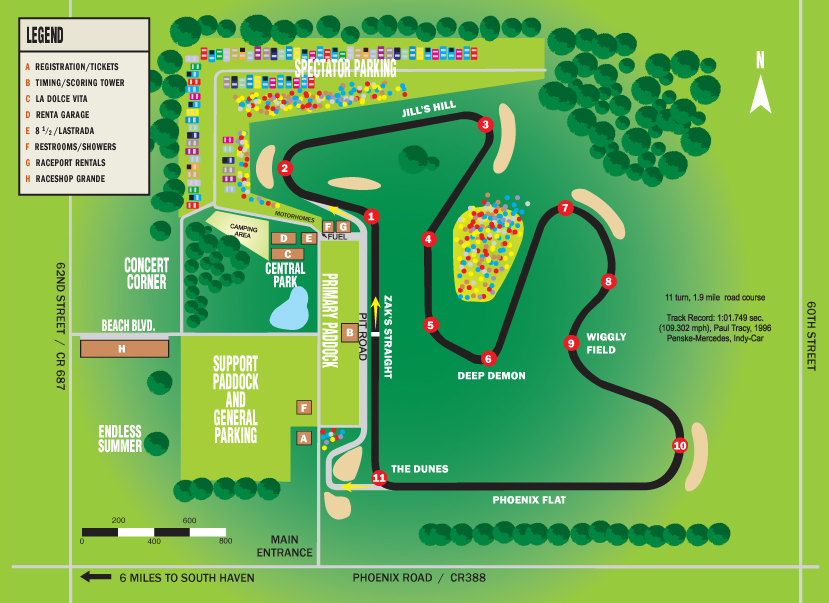

Illustration 4 Layout of Grattan Raceway

Lessiter Road is just off to the right. The building indicated as "Registration" is the entrance to the property. Kurt Faasen lives upstairs over the registration area. Grattan features a nice swimming pool for the use of groups renting the track and it is located just behind Registration. The building also contains showers and bathrooms for campers.

E.J. and Mary Faasen live over the building designated "Tech Garage". This building also contains bath rooms and showers for those camping in the paddock and the food concession and offices. Road races are run clockwise, so turn 1 is the sharp right hand turn just below the Registration building in the illustration. Turn 3, a sharp left turn is the downhill "reverse camber" turn. Turn eight, at the top left of the picture is a "blind apex" corner; the track is bowl shaped through the turn and a driver must steer sharply to the right, committing the car at high speed to a certain line without being able to see the spot he is aiming at on the other side of the corner.

The tower is built on top of the right end of the building marked "Garages". The garages are available for rental on race weekends for those who want to be sure to be out of the elements while working on their cars.

Illustration 5

Illustration 2 E.J. Faasen in 2002

E.J. Faasen in 2005, on the deck outside the residence. Part of the long straightaway is near the top of the picture and the Registration building is at the very top of the picture.

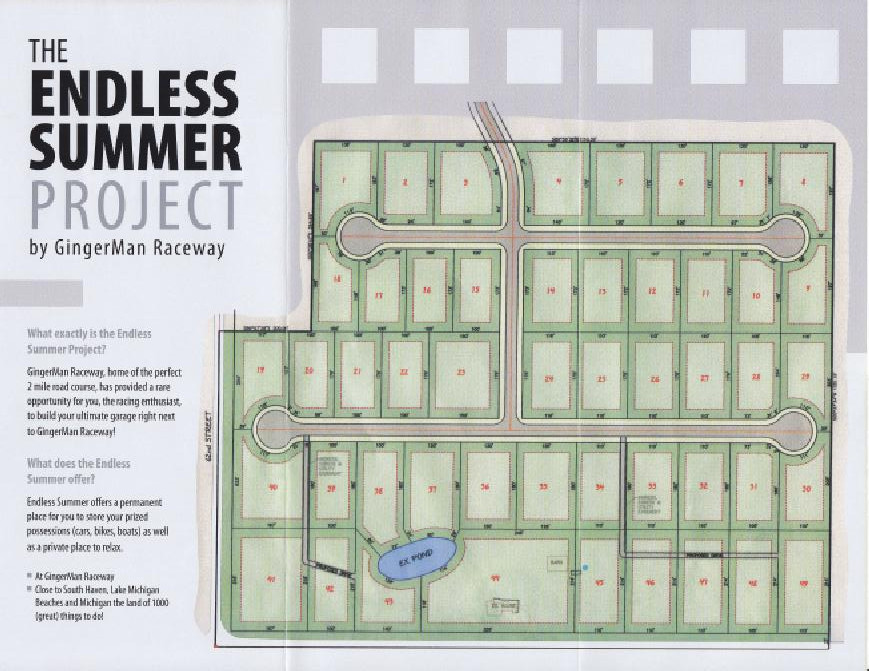

GINGERMAN RACEWAY

The GingerMan Tavern in Chicago is about a block north of Chicago landmark Wrigley Field, in what is known locally as Wrigleyville. But the GingerMan is most emphatically not a sports bar; there is one television and it is usually tuned in to local news. Jazz and blues usually comes from the bartender operated music system, played at a level that permits easy conversation. The GingerMan is located next to The Metro, a legendary institution in popular music in Chicago where many nationally known musical groups began their careers. The Metro, which occupies a four story building, was designed to attract a bohemian, arts oriented crowd and that clientele patronizes the GingerMan. Large numbers of baseball fans do patronize the bar also, but groups of drunk, rowdy baseball fans are greeted with loud classical music on the sound system, which usually solves the loud, drunken baseball fan problem. (Illustration1)

The bar is surrounded by specialty restaurants of every description and menu and does not serve food itself. Regulars know they can bring in food purchased at any of several local specialty restaurants. The emphasis is on an extensive collection of specialty and micro-brew beers, a menu in which the GingerMan was a Chicago pioneer. The space is triangular and is bisected by the bar; the building fits the sharp angled intersection of blank and blank. There are pool tables in the back half which are free on Sundays. The service is excellent, the bartenders knowledgeable and competent and the staff is neat, personable and well trained. The business concept is well defined, well executed and the owner's expectations are high.63

Dan Schnitta, a Chicago business man with other interests founded the GingerMan in 1977. The namesake of the bar is the main character in the J. P. Donleavy novel about "…An American hitchhiker in Europe with a taste for liquor, women and roguish behavior" 64

The novel reminded Dan of his own youthful travels in Europe. But he became involved in road racing back in Chicago in the company of business associates who introduced him to a local Porsche club. He first attended sports car events, then bought a sports car himself and finally started participating, eventually racing throughout the Midwest. Driven by the same ambition reflected in the bar, Dan purchased a small track in Michigan, to have a place to race the way amateur racing should be done. Before long Dan's concept of what a track should be was forming, but the township where the first track was located would not cooperate with his plans for improvement and expansion. Passionately devoted to sports cars and racing, with a solid business method and success behind him, Dan looked for a new location.65

Gingerman Raceway opened in nineteen ninety six, located five miles east of South Haven, Michigan. A prime prerequisite for the site, in a rural, sparsely populated spot, was that the township had no zoning restrictions. The gently rolling terrain permits subtle elevation changes, prized by road racing drivers. The land, three hundred and sixty acres, proved to have substantial deposits of sand, crucial to a properly constructed track and provided room to design a track. Grattan Raceway, discussed above and Waterford Hills, discussed below were both "designed" to use as much available land as there was at those sites; that is, they were drawn to fit what there was available. The site for Gingerman was chosen to make available as much land as Dan Schnitta's exacting expectations would require.

Schnitta hired an internationally known designer, Alan Wilson, to design the track. Wilson had been a racer and had managed some famous racetracks in England before moving to the United States to start his design firm. He has gone on to design numerous new race tracks and has redesigned or modified several well known American tracks. The design provided for future expansion. Schnitta hired an engineering firm to supervise construction, but dismissed it when he decided he and Wilson could act as general contractors, using local firms to do the work. Dan has hired local firms to do the work at Gingerman ever since.

In the press release announcing the first full season, the designer commented on the owner's insistence on safety. Dan Schnitta's attitude was and is that the track design should mitigate the dangers of motor racing to the greatest extent possible. Amateur racers want the thrill of speed and the intensity of competition; but racing is 'Not All But Their Lives', to paraphrase Stirling Moss' title for his biography.66 Schnitta feels that a demonstrably safer track opens the sport up to people who would not participate otherwise and he takes great pride in the assertion that no car driver has ever spent a night in the hospital as a result of competing at Gingerman.

As may be seen in Illustration 2, each corner features a gravel trap, similar to the sand traps found on golf courses at the outside of each corner. A car out of control comes off the corner and if not corrected quickly enters the trap where the fine gravel slows or stops the car before it can hit anything solid. There are no trees on the track and the only steel Armco barrier separates the pit entry lane from the front straight away. The verge of the track, the edge where the racing surface ends and the grass begins has been carefully contoured so that there are no edges to exacerbate loss of control and no abrupt transitions to cause a car to roll over or launch into the air. Care was taken to see that there are no decreasing radius turns on the track, a geometrical feature of the design that might facilitate a car's spinning in a circle and even coming back to the track facing the wrong way. (Illustration 3) Everywhere on the track the experience of the racers who designed it is evident. Cars are expensive and lives and health are precious and the track makes every possible effort to mitigate the dangers of racing.

In a way Gingerman reaches back to Janesville Airport. The open layout allows for greater safety, visibility for drivers, workers and racers and yet the subtle elevation changes and careful layout provide a racing experience far beyond a flat, sharp angled airport. The shape of the property allows a spectator area on top of a modest hill where spectators can follow an exciting duel between competing cars all the way around the track. Modern bathrooms with showers, a small convenience store, meeting room and picnic and camping grounds are all presented on a well manicured, landscaped park like setting and together offer all the amenities week end racers and spectators desire.

The GingerMan Tavern has Wrigley Field and The Metro. Gingerman Raceway has South Haven Michigan six miles to the west on Phoenix Road. South Haven is a beautiful resort town located on Lake Michigan. Typical of Lake Michigan resort towns it has a resident working population and a resort population that swells in spring, summer and early fall. The City features many restaurants, bed and breakfast resorts, a harbor busy with yachts in season and a lively social scene. Between the track and the town, along Interstate 196 there are chain restaurants and motels for those who only want to sample the resort ambience. Nearby are the twin cities of Saugatuk - Douglas, an area described as the Midwest's Cape Cod. Inland lies the Fenn Valley vineyard, one of several of southwest Michigan's wine country establishments. Chicago is less than three hours away, Detroit less than two. One suspects there was more to the site selection process than the lack of zoning restrictions, although that expectation was met as well.